Professors describe fear amid Trump pro-Palestine activism crackdown

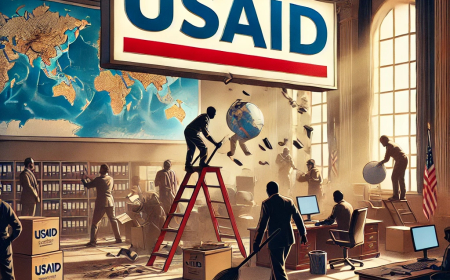

Two green card-holding professors at American universities on Monday took the stand to detail how they grew fearful and less willing to publicly criticize the Trump administration as it began targeting pro-Palestinian campus activists. The testimony came during a bench trial in federal court in Boston over the government’s crackdown, namely a policy that...

Two green card-holding professors at American universities on Monday took the stand to detail how they grew fearful and less willing to publicly criticize the Trump administration as it began targeting pro-Palestinian campus activists.

The testimony came during a bench trial in federal court in Boston over the government’s crackdown, namely a policy that has led to arrests and efforts to deport foreign-born students and faculty members linked to campus demonstrations.

After the arrest of former Columbia University pro-Palestinian activist Mahmoud Khalil, Megan Hyska texted a colleague that she felt like she was “climbing the walls,” a way to describe the “extremely stressed out, scared (and) maybe a bit trapped” feelings she was experiencing.

A Northwestern University philosophy professor and Canadian citizen, Hyska testified that Khalil’s arrest and the arrest of Tufts student Rümeysa Öztürk rang alarm bells that she could be similarly singled out.

“It became apparent to me after I became aware of a couple high profile detentions of student activists ... that my engaging in public political dissent would potentially endanger my immigration status — that I risked detention and deportation for being publicly politically critical of the Trump administration,” Hyska said.

Khalil’s detention in March was the first in the Trump administration’s clampdown on foreign students with ties to pro-Palestinian activism on college campuses, whom Secretary of State Marco Rubio deemed threats to the nation’s foreign policy. He remained detained until a judge last month ordered his release.

Hyska called it “shocking” that Khalil’s green card-status did not “protect him from this treatment.” A Truth Social post by President Trump, which derided Khalil’s views and said his was “the first arrest of many to come,” made the professor believe that his detention was solely underpinned by his political speech.

When Öztürk was detained, Hyska saw her students and herself in the doctoral student. That feeling grew “more acute” when she learned the doctoral student was detained in part over an op-ed in Tufts’ student newspaper.

“Particularly because I myself had been recently drafting an op-ed that was critical of the Trump administration,” Hyska said.

But Hyska’s op-ed was never published. She determined it “would not be safe” to release it.

After that, Hyska said her political activism diminished.

She signed a petition under a pseudonym, turned down leadership positions with the Democratic Socialists of America and planned to reassess her Northwestern syllabi to cut back on “risky” topics. She also declined to attend protests of the Trump administration or wore a mask to conceal her identity. And she said she won’t return to Canada for now, fearing extra scrutiny upon trying to reenter the U.S.

Nadje Al-Ali, a professor of international studies, anthropology and Middle East studies at Brown University, took the stand next. A German citizen, Al-Ali said she is one of many in her generation to retain a “historical awareness” of the Holocaust and Nazi Germany, which has “very much informed” her thinking, academic interests and morals — especially in knowing that “being silent could mean complicity” in some situations.

The arrests of Khalil and Öztürk marked a turning point for Al-Ali, as well. She had left the U.S. on March 8 to visit her mother in Germany, and the next morning, saw the news of Khalil’s detention. She wondered: “What’s going to happen when I get back?”

“Although these were students, I felt like, ‘Okay, next in line will be faculty,’” Al-Ali said. “So, I definitely felt vulnerable and targeted as a result.”

Though Al-Ali was scheduled to go to Switzerland and then Italy following her visit with her mother, she said she instead returned to the U.S. after contacting an immigration lawyer to track her journey back.

She later canceled trips to the Middle East for research, concerned that reentry to the U.S. from those countries would “raise red flags” and make her seem “more suspicious.” A feminist critique of Hamas she planned to write was also shelved because she would also have critiqued Israeli government policies through that lens.

“I felt that was too risky,” Al-Ali said.

The Brown professor also said she wanted to attend several protests of the Trump administration but feared retaliation.

During Hyska's cross-examination, Justice Department lawyer William Kanellis suggested that her speech was not truly chilled. He pointed to talks and political meetings she attended since the crackdown began and a politically charged letter she signed onto that was sent to Northwestern’s administration leadership. He also noted that the government had not targeted her in any personal way.

Hyska pushed back that the letter was to Northwestern, not the public, and the Trump administration’s policies have still made her “afraid to speak out.”

The government has not yet had the opportunity to cross-examine Al-Ali.

The lawsuit, brought by several university associations, centers on the policy underpinning the attempted deportations.

The statute invoked by Rubio makes deportable any noncitizen whose “presence and activities in the United States” is deemed to have “potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences” by the secretary of State. However, the statute contains a safe harbor that blocks deportation based on their beliefs or associations.

The plaintiffs say the Trump administration’s focus on students and faculty who have opposed Israel’s war in Gaza violates that exception: They’re not challenging the constitutionality of the foreign policy provision.

Hyska said she experienced “considerable trepidation” about testifying because of the target it could put on her back. But she said she felt she had to take the stand so that the challenge to the administration’s crackdown could proceed.

“If noncitizens aren't willing to take the risk, it won't move forward at all,” she said.

What's Your Reaction?